Arriving in Hue, Central Vietnam, I can immediately see the difference from the north. It’s calmer, more relaxed, the people are friendlier and the streets cleaner. Hue is a huge city with a lot of history, specifically regarding the Vietnam War. I am a little wary on how they would receive Americans, as one should be in every country that has been hit with about seven million tons of American bombs in a ten year period. I sign up for a personalized tour of the city on the back of a motorbike for $10, and thats how I meet Bill.

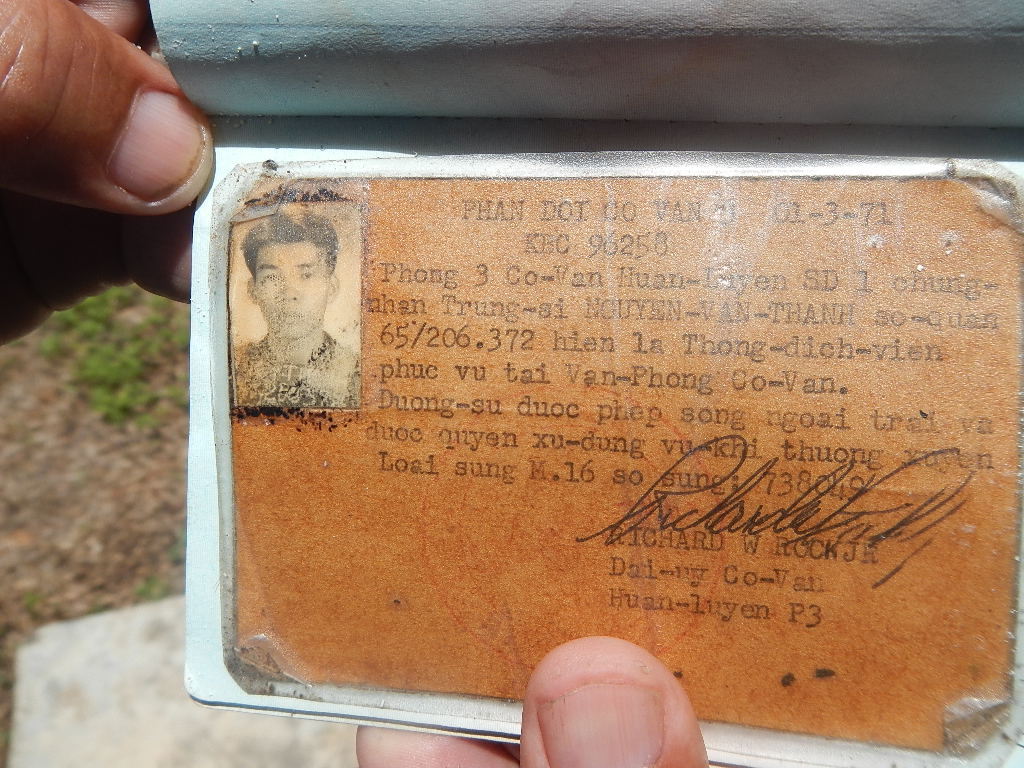

Bill picks me up on the biggest motorcycle I’ve ever seen sporting an American flag and a huge smile. The local tour company, Easy Riders, had connected us. Easy Riders employs Vietnam veterans to take tourists around the south and tell them their story. At 21, Bill became a translator and advisor for the US marines from 1966-1973. He worked for the Americans, he is very clear about that. When I ask if he was also a part of the southern Vietnamese army, he yells, “No, American only!” His boss was American, his fellow marines were Americans, but he is Vietnamese. He didn’t say so, but I have a feeling his real name is something quite different, but Americans couldn’t pronounce it so they started calling him Bill. He’s quite proud of his past, and considers himself an American citizen. However, I can sense some underlying bitterness towards America as well. When the war ended, the south had surrendered, the American marines packed up their stuff and took off in helicopters, leaving a complete mess of the surrounding region, and leaving Bill. As he watched his fellow marines fly to freedom, he was imprisoned for several months. After being released, he wrote to the US embassy in Saigon for five years, asking for a visa to move to the States, and never heard back.

He takes me to all the major sites in Hue, which aren’t very impressive. Not Hue’s fault, the Americans had heavily bombed the city, and its famous imperial citadel where the Viet Cong hid out. Bill shows me a local farming village where an older woman demonstrates how rice is made. I also visit an artist studio; like in other communist countries, art is a way to disguise political opinions. I end the day sipping beer with Bill and his friends. I am glad to ride on the back of his motorcycle, because in this crazy Vietnamese traffic, you wouldn’t want to drive.

He takes me to all the major sites in Hue, which aren’t very impressive. Not Hue’s fault, the Americans had heavily bombed the city, and its famous imperial citadel where the Viet Cong hid out. Bill shows me a local farming village where an older woman demonstrates how rice is made. I also visit an artist studio; like in other communist countries, art is a way to disguise political opinions. I end the day sipping beer with Bill and his friends. I am glad to ride on the back of his motorcycle, because in this crazy Vietnamese traffic, you wouldn’t want to drive.

But the next day I rent a motorcycle of my own and follow Bill and another girl to the DMZ, which is about a three hour ride outside of Hue, on Highway One or what tourists call the “death highway”. I quickly discover why, as semi trucks pass each other taking up both lanes of a bridge while bikers squeeze to the side. When a truck passed me coming so close it brushed my elbow, I decide that this is a terrible idea. The DMZ, or Demilitarized Zone, was the dividing line between the north and south during the war, at the “17th parallel”. No combat was to take place here, (although the Americans dropped three thousand bombs on it). Military leaders could meet and have negotiations here, families could reconnect in this area safely.

As we walk around the 17th parallel bridge, Bill explains that even today it is still dangerous to speak positively about the south; twenty dissidents were imprisoned recently, and as he explains this he looks over his shoulder. Around the DMZ are the Vinh Moc Tunnels, a complex that stretches about 2,000 meters long and 30 meters

deep, with seven entrances and three different levels, all underground. Five hundred Vietnamese soldiers lived in these tunnels with their families, children were born here and an entire village thrived underground. The tunnels were a fascinating aspect of the war to explore, and as an American, I found it really important to see first hand the impact of our wars.

~ By Teresa Murphy of Tess Travels. Murphy visited the Thaipsum Festival, a Hindu ritual that takes place every year in the Batu Caves outside of Kuala Lumpur.