On my recent visit to Turkey with The Atlantic Institute, I had the opportunity to learn about America’s favorite poet, Rumi. I visited Rumi’s tomb and museum in Konya, heard his philosophies at the Mevlana University, chatted with a real life dervish, and attended a whirling dervishes performance at the cultural center in Konya.

Jalāl ad-Dīn Muhammad Rūmī (1207-1273) was born to Persian parents in a village which is now located in modern day Afghanistan. Rumi’s poetry spread across Persian countries and influenced literature and lanugages such as Persian, Turkish, Urdu, Punjabi, Pashto and Sindhi.

Rumi’s father, Baha’ ud-Din, was a world renowned scholar who later became the head of a madrassa (religious school). After this death, 25 year old Rumi inherited his position as the Islamic molvi. Rumi practiced Sufism as a disciple of Burhan ud-Din, became an Islamic Jurist, issuing fatwas and giving sermons in the mosques of Konya. He also served as a Molvi (Islamic teacher) and taught his adherents in the madrassa.

Rumi was buried in Konya, Turkey, and his shrine became a place of pilgrimage. Following his death, his followers and his son Sultan Walad founded the Mevlevi Order, also known as the Order of the Whirling Dervishes, famous for its Sufi dance known as the Sama ceremony. Rumi believed passionately in the use of music, poetry and dance as a path for reaching God. For Rumi, music helped devotees to focus their whole being on the divine and to do this so intensely that the soul was both destroyed and resurrected. It was from these ideas that the practice of whirling Dervishes developed into a ritual form.

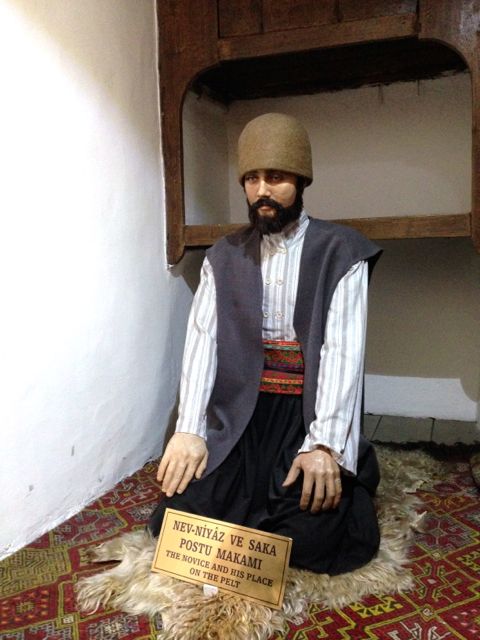

The Mevlâna Museum in Konya, was once a dervish lodge where students and teachers lived and practiced the Mevlevi Order. New students had to sit in stillness for 3 days while they were tempted by the sounds and smells of the kitchen. Once they passed this test, there was another 1001 days of training, followed by 40 days of testing, before one qualified as a Dervish. At the museum, one can visit the Dervish quarters, see their costumes and other memorabilia, and get a sense of the life they led.

The Dervishes wear a long white robe symbolizing shrouds of ego. At the beginning of the ceremony, the black cloak is discarded to signify their liberation from the attachments of this world. The tall camel’s hair conical felt hat (called sikke) literally translates to “tying down an animal” or controlling animal instincts and letting go of feelings. They whirl from right to left because, they believe God lives in the heart (which is on the left side) and one should never loose the connectivity. There are no strict regulations or techniques in whirling, although you would typically see the right arm up reaching out to the sky ready to receive blessing, and the left hand directed toward earth, keeping him grounded. Once the Dervishes start, they just allow their bodies to let go and take whatever form it likes.

Just outside the premises are what appear to be souvenir shops, but many are craftsmen working with felt, silk, pottery and more. I walked to the second floor of Kece Sanat Evi felt art house, owned by a real life Dervish. Jalaluddin started his practice at the age of 6, as everyone in his family did. He went on to study Whirling in Istanbul and Bulgaria, mostly for himself. Now, he practices on certain religious days, at home when he feels like, or even sitting down.

“The electrons, moon, galaxy, entire universe is whirling, and when we whirl, we become attuned to our surroundings”, says Jalaluddin. He described the experience mediation-like, where he looses track of time or control over his body. It is an expression of feeling thankfulness for everything around you and to God. The main belief of the Order is to not question creativity and your reason for existence, but appreciate what’s around you. This is sought Through abandoning one’s ego or personal desires, by listening to the music, focusing on God, and spinning one’s body in repetitive circles, the Dervish aims to reach the source of all perfection, or kemal.

With the foundation of the modern, secular Republic of Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk removed religion from the sphere of public policy and restricted it exclusively to that of personal morals, behavior and faith. On 13 December 1925, a law was passed closing all the tekkes (or tekeyh) (dervish lodges) and zāwiyas (chief dervish lodges), but now Whirling Dervishes are seen as a cultural tradition and allowed to practice only for the sake of music and dance.

In Konya, there is a free performance every Saturday evening at the Konya Cultural Center, which is worth attending. Watch the video below…