The Kingdom of Bhutan is a tiny Buddhist country located between two emerging superpowers, China and India. How is it that it manages to retain its stance on measuring the country’s progress based on GNH (Gross National Happiness) vs GDP (Gross Domestic Product)? Are the people in Bhutan truly happy, and why? These are some of the questions I was eager to get answers to during my recent visit to Bhutan.

At first glance, I saw a lot of poverty, undeveloped infrastructure and lack of resources even in the country’s capital, Thimphu. There were a few hotels and restaurants, the shops were selling television sets one found in the 1980’s, cars were freely emitting exhaust, and people throwing garbage out their windows. When I walked into souvenir shops, I wasn’t greeted or welcomed, and attended to only when I asked something. On the streets, people had serious faces and went about their daily business. From an outsider perspective, I would say these were not signs of happy people.

However, when I had one-on-one conversations with people and asked them about the meaning of happiness, they gave me a refreshing response. The Bhutanese people grow up in a Buddhist lifestyle. They pray everyday, believe in karma (which includes doing good, not harming animals, taking care of the environment), and furthering their lives collectively. They live as a community and everyone comes forward to help each other in times of need, be it death, birth or illness. There is a strong sense of culture which is reflected through their lifestyle, costumes, and celebration of festivals.

However, when I had one-on-one conversations with people and asked them about the meaning of happiness, they gave me a refreshing response. The Bhutanese people grow up in a Buddhist lifestyle. They pray everyday, believe in karma (which includes doing good, not harming animals, taking care of the environment), and furthering their lives collectively. They live as a community and everyone comes forward to help each other in times of need, be it death, birth or illness. There is a strong sense of culture which is reflected through their lifestyle, costumes, and celebration of festivals.

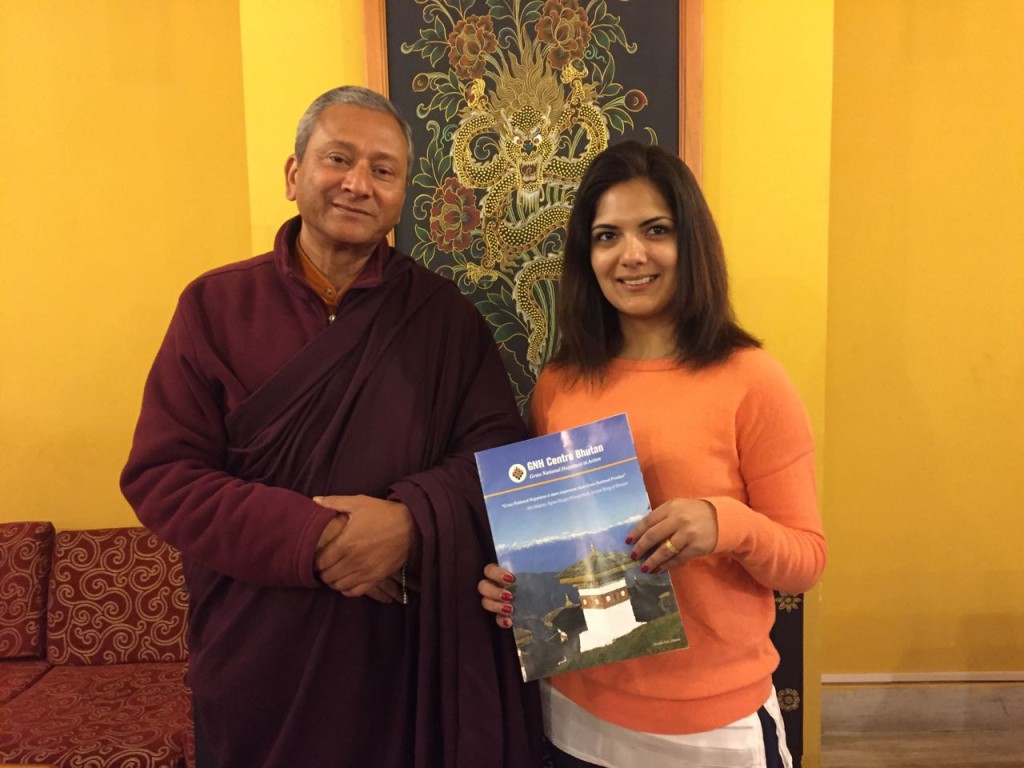

I also interviewed Mr. Saamdhu Chetri, executive director at Gross National Happiness Centre. He told me that the idea of GNH was started by the 4th king of Bhutan who studied at Cambridge and traveled extensively. The King realized that people in the western world had much too consume, but weren’t really happy. He decided to create a new framework for his own government, in which he would focus on the well being of his people and the country’s resources, rather than how much they can produce. He appointed a team of statisticians, psychologists and ministers to create standards of measuring happiness i.e. GNH index based on 33 questions. The index surveys all citizens of the country on psychological wellbeing, health, education, time use, cultural diversity and resilience, good governance, community vitality, ecological diversity and resilience, and living standards. They survey does not measure income.

Here are some of the results the GNH Index reveale about happy people of Bhutan:

- Men are happier than women on average.

- Of the nine domains, Bhutanese have the most sufficiency in health, then ecology, psychological wellbeing, and community vitality.

- In urban areas, 50% of people are happy; in rural areas it is 37%.

- Urban areas do better in health, living standards and education. Rural areas do better in community vitality, cultural resilience, and good governance.

- Happiness is higher among people with a primary education or above than among those with no formal education, but higher education does not affect GNH very much.

- The happiest people by occupation include civil servants, monks/anim, and GYT/DYT members. Interestingly, the unemployed are happier than corporate employees, housewives, farmers or the national work force.

- Unmarried people and young people are among the happiest.

- There is quite a lot of equality across Dzongkhags (districts), so there is not a strict ranking among them. The happiest Dzongkhags include Paro, Sarpang, Dagana, Haa, Thimphu, Gasa, Tsirang, Punakha, Zhemgang, and Chukha.

- The least happy Dzongkhag was SamdrupJonkhar.

- The ranking of dzongkhags by GNH differs significantly from their ranking by income per capita. Sarpang, Dagana, and even Zhemgang for example, do far better in GNH than in income.

- In terms of numbers, the highest number of happy people live in Thimphu and Chukha – as do the highest number of unhappy people!

- Thimphu is better in education and living standards than other Dzongkhags, but worse in community vitality.

The results are used by the kingdom and the government to make decisions regarding administrative policies, planning, resource allocation, monitoring and evaluation of development. They use the survey results to prepare strategy for the country’s development with values that includes equality, kindness, humanity, screens policies and measures sufficiency in every Bhutanese life. As a result, education is now freely available to even the remotest locations of Bhutan.

The results are used by the kingdom and the government to make decisions regarding administrative policies, planning, resource allocation, monitoring and evaluation of development. They use the survey results to prepare strategy for the country’s development with values that includes equality, kindness, humanity, screens policies and measures sufficiency in every Bhutanese life. As a result, education is now freely available to even the remotest locations of Bhutan.

When compared to other happy countries of the world (such as Denmark, Finland), Bhutan doesn’t compare as those ranking account for economic prosperity as well. Bhutan being a small third world country, where hardly anything is manufactured or exported from, does not stand a chance.

According to my understanding, happiness is a difficult thing to measure. When you ask someone, “Are you happy?” most people respond “Yes”. It is also subjective. On the other hand, mental, physical and spiritual wellbeing are more reasonable measurements that defines if the environment hold all the factors that would enable someone to be happy. It is good to know that the basic principal of Bhutan is to govern based on the citizen’s well being and many countries are now looking towards Bhutan for advice on the same. Mr Chetri himself has been meeting with global leaders to consult them on how to implement the concept in their own countries.